India’s real estate sector has witnessed two cycles over the past 15-20 years, during 1994-99 and 2004-09. Both cycles had unique characteristics, yet displayed notable similarities in the manner of their occurrence. A walk through these cycles reflects some of these peculiarities and distinctions, and helps to gauge the changing dynamics of this industry.

India’s real estate sector has witnessed two cycles over the past 15-20 years, during 1994-99 and 2004-09. Both cycles had unique characteristics, yet displayed notable similarities in the manner of their occurrence. A walk through these cycles reflects some of these peculiarities and distinctions, and helps to gauge the changing dynamics of this industry.

|

|

Period 1994-99: Industrial Boom – The First Known Real Estate Cycle

The genesis of India’s industrial boom, which began in 1994, can be traced back to the 1991 liberalisation reforms that were undertaken by the ruling Government of the day against the backdrop of a looming fiscal deficit crisis in the country. In addition to several other steps, investments in the real estate sector were opened up for the participation of Non-Resident Indians (NRIs) and Persons of Indian Origin (PIOs) for the first time.

The massive investments into the sector that followed coincided with a broader economic and stock market boom. Developers started aggressively reaching out to the NRI / PIO community by opening offices in major NRI-resident countries. The policy-driven bullish cycle culminated in an industrial boom, thereby helping property prices to finally peak in 1995.

However, at this peak, some of the crude realities of the Indian economy started to resurface. Poor banking penetration, high domestic interest rates, a lack of transparency in the real estate sector and insufficient availability of market information, etc. led to a rally in real estate. As a result, the market tapered off post-1995. In 1997-98, the advent of the Asian Financial Crisis (AFC) led to a slo9wdown in industrial growth, wiping out an important source of this investment cycle – foreign capital.

Period 2004-08: Services Boom – The Second Real Estate Cycle

The second known cycle began in 2004, again having its roots in critical reforms that took place in the previous 4-5 years. The new Telecommunication Policy, 1999 and the Information Technology Act, 2000 gave rise to an era of digitisation, creating a favourable investment climate and ample job opportunities across many Indian cities. For the first time, real estate development expanded beyond the Tier I cities, unlocking opportunities in the commercial as well as the residential property sectors.

In 2005, the Special Economic Zone (SEZ) Act and the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM) – which facilitated huge investments into building infrastructure to connect larger cities with 60+ smaller cities and towns – provided a fillip to investment sentiment. The full opening up of FDI into selective real estate projects provided a thick layer of icing on the cake.

Consequently, multinational investors queued up for exposure into the Indian market – rather prematurely, as has been pointed out by Goldman Sachs in its famous report on Brazil, Russia, India and China (the BRIC report) in 2004.

Institutional funding invested in virtually every commercial development, largely offering developers equity-style funds. Developers had no problem funding residential projects, owing to healthy cash flows from preconstruction bookings. Rising salaries coupled with low interest rates and increased banking penetration converted every homebuyer into an investor, as properties were bought not merely for consumption but for investment even by the salaried class.

Following the peak of the second cycle in 2008 was a large accumulation of debt with almost every stakeholder – developers (having accumulated land parcels at increasing prices), small investors / homebuyers (stretching loans to purchase additional houses), banks (holding stakes with buyers and developers) and institutional investors (holding stakes with developers).

Globally, the collapse of Lehman Brothers triggered a panic, leading investors to scout for rationality in investments across asset classes. The ensuing economic slowdown and risk of job losses made it difficult for investors to exit from their stakes. For instance, ~80% of investments that came via the Private Equity (PE) route since 2006 are yet to find a good exit.

However, despite a steep slowdown in the Indian economy and financial markets following the outbreak of the crisis, housing prices in India – on an average – witnessed a limited fall. On the contrary – prices started to rise after 2-3 quarters of sharp fall, and even crossed the previous peak of mid-2009.

Similarities In Both Cycles

- Both cycles were created out of favourable policies and a positive investment climate – both domestically and globally

- Both cycles had an important share of funding from external source – NRIs / PE investors

- Both cycles collided with the economic and financial boom-bust cycles

Differences In Both Cycles

- The bullish uptrend in prices during the second cycle was longer than that of the previous cycle

- The bearish downtrend in prices during the second cycle was shorter than that of the previous cycle

- At the end of the second cycle, there was no prolonged period of stability in prices post-crisis

Housing prices breached their previous peaks merely a year after the bottom in 2009, while vacancy rates have continued to remain high

| Cycle timelines | 1994-99 | 2004-08 |

| Beginning of the cycle until peak (uptrend) | 1.5 years | 3.5 years |

| Peak to the end of the cycle (downtrend) | 4.0 years | 1.0 year |

| Lateral price movement (stable prices) | 4.0 years | Not more than 6 months |

The Second Cycle May Be Yet To See Meaningful Conclusion

When we compare these two cycles, two obvious differences suggest that the second cycle may not be over as yet. In the first place, prices recovered almost immediately after reaching the so-called trough without witnessing a meaningful period of stability. Secondly, the wide gap between the duration of up-cycle as well as down-cycle could possibly indicate that the latest cycle is yet to witness an end.

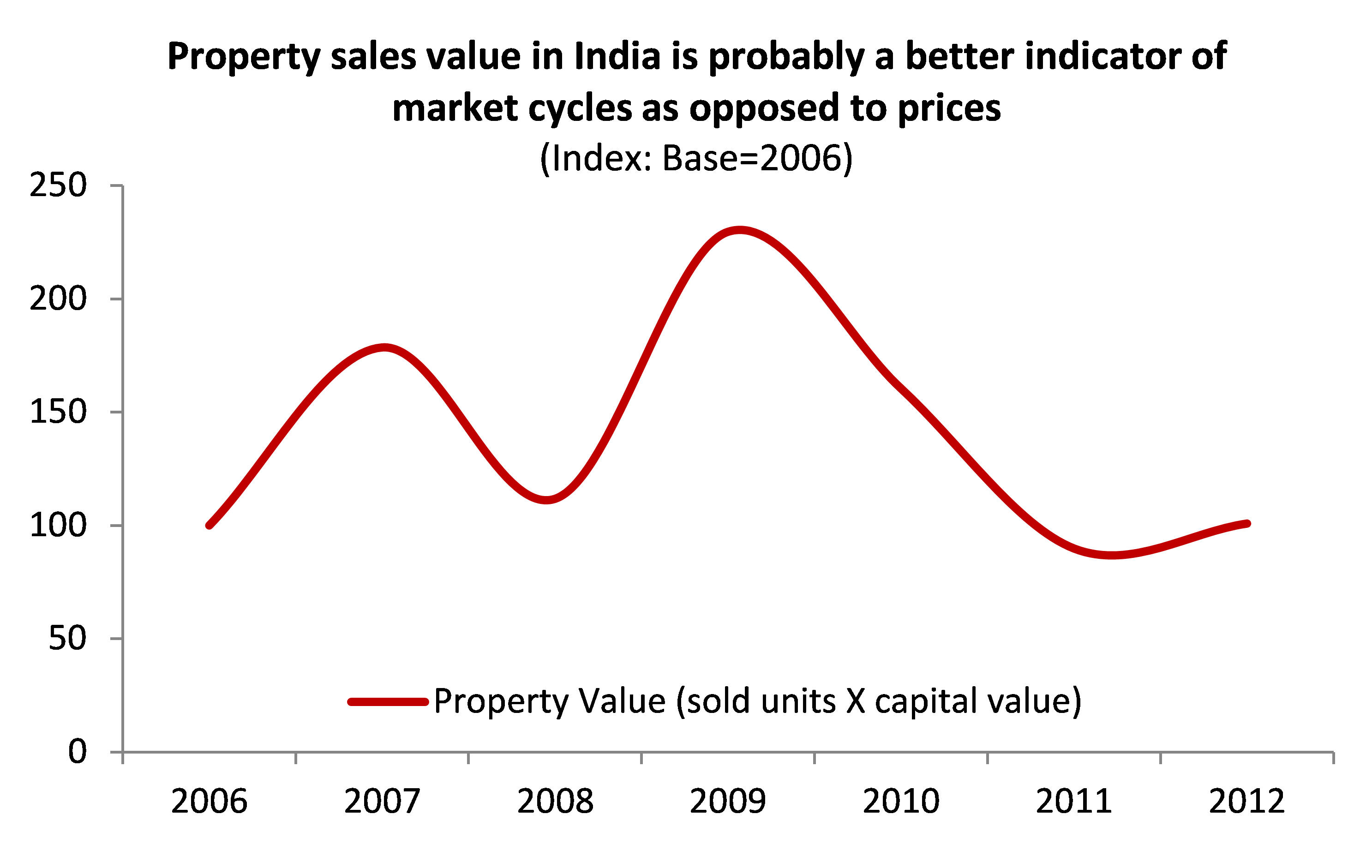

This leads to a logical question – have real estate prices failed to reflect market realities of late? The answer is a resounding yes. To check, we derived the value of properties sold using net absorption, and fond that the recovery in this sector only started post-2012 and that the duration of the second cycle is much longer than the prices indicate.

The Indian economy has reached its new-normal rate of growth. The country’s total property sale values have also reached an elevated new normal level, and we believe they will continue to sustain at this level in the near-to-medium term. This is because recent trends and the foreseeable outlook suggest that the volume of sales will rise as developers focus on mid-segment and affordable homes. On the other hand, increased focus on affordable to mid-segment housing would help bring the average prices down, hence retaining the value of properties.